A History of Changing Attitudes

As liberal-minded as today's art connoisseurs may be, their views regarding nudity pale when compared to the broad attitudes of ancient Greece and her worship of unclothed Hellenistic gods. Modern civilization has yet to become comfortable with the bare human form to a level where it can embrace physical beauty as publicly displayed works of art or be as comfortable as the pre-Christian Greeks with naked (gymnos) Olympian sporting events [1].

Classical Greek art would climax after the death of Alexander the Great (323 BCE) and last almost two centuries until the Roman conquest of the Greek peninsula (146 BCE). The idealized Greek figure was an embodiment of grace and health, beauty, and vitality. For the ancients, the ennoblement and perfection of their natural human state remained a matter of pride and self-assurance.

Subsequently, the appearance of sculpted genitalia or unclothed athletes was a celebration of human beauty, one which issued no negative response or repulsion. To the Athenian mind, clothing was simply decorative, for practical protection or a class distinction. To consider refined works of sculpted or painted figurative arts immodest would have been an uncultured, barbarian [2] response.

Hellenistic Figures

After Greece came under Roman rule, its artwork, including statues of Hellenistic deities would often be confiscated and imported along with Greek artisans [3] to sculpt, create mosaics, and paint murals of Roman variations on Hellenistic theology. This Roman period of Hellenistic art would often produce sculptures that included highly detailed figurative monuments of Rome's emperors and officials (figure to right). However, even with its high level of finish, ancient Rome would never quite eclipse the earlier Athenian golden age of the human form.

Nevertheless, adoration of the idyllic human form would eventually clash with the chaste modesty of Christian theology and supply fuel to the reverse-persecution efforts of the early Christian Church towards its longtime pagan rivals. The consequences of which was a wholesale rejection of Hellenistic imagery and the willful destruction and disfigurement of ancient masterworks.

Once Christianity spread across Western culture, rendering the unclothed human figure would slow down or cease entirely. Aside from the few surviving frescos and carved symbols found in the Roman catacombs, Christian artwork is barely present until the 4th century. By that time, the relatively new religion had become legalized (Edict of Milan, 313 CE) within the Roman Empire. Later that same century Christianity became the Empire's state religion (Edict of Thessalonica, 380 CE).

The New Religion

As the Abrahamic views of Judaism, Christianity, and eventually Islam began to overwhelm and replace ancient polytheistic sensibilities, all figurative artwork would become forever challenged. With the advent of monotheism, the unveiled natural human form became sinful, wrong, even evil. Male and female gods and goddesses (lower-case g) were replaced by a singular male God (upper-case G). Consequently, no longer a partner of Zeus in the heavens, the social status of the earthly bound female, daughter of Eve, plummeted to that of a second-class citizen, subservient to the now spiritually enlightened male.

[4]. With the exception of Yahweh becoming a godhead composed of itself, a son, and a spirit, the original Christians faithfully continued to follow all Jewish religious traditions and rites, which excluded religious imagery [5]. However, when the disciples of Jesus attempted to convert their Jewish brethren, they discovered considerable resistance. Ultimately, they were forced to turn to pagan gentile recruits or have the "new" faith die out [6][7].

Like the Jews (and the later Muslims), not all early Christians embraced religious artwork [9]. However, once gentiles gathered majority rule within the new religion, the Hellenistic tradition of sculpted and painted deities would slowly re-emerge, but not without ongoing resistance and setbacks.

Deadly Toys

By contrast, the unclothed human form is far more acceptable today than during the days following the fall of Hellenistic culture. From an aesthetic standpoint, chastity or the restriction of nudity to the marital bed chamber would become more of an Abrahamic/religious concept.

Even before Emperor Constantine's Edict of Milan of 313 CE, which freed Christians from government persecution, the new religion had spread rapidly across the Roman Empire. Still remembering the faith's Jewish roots and the history of Hellenistic persecution, Clement of Alexandria (150-215 CE), one of the early Church fathers and theologians, referred to all visual arts (not just nudes) as "deadly toys" [9]. However, bear in mind most art up until that time was Hellenistic depictions of Olympian gods, usually unclothed, or non-religious erotica.

Clement went on to criticize the pagan deities themselves for being "bad examples and warnings of what to avoid" [10]. This emphasis on morality and puritanical behavior would become central to Christianity's developing theology. Clement and other church fathers would go to great lengths to distinguish themselves from their Hellenistic, pagan rivals. In one somewhat humorous instance of this extreme, Clement stated: "Let the head of (Christian) men be shaven unless he has curly hair..." [11].

This inevitable polarization was the result of centuries of persecution and mistreatment at the hands of Hellenistic officials. Consequently, in territories where Christianity became dominant, pagan artwork was often mutilated or destroyed. However "nonhuman pagan representations" (vases, animal sculpture, carvings, etc.) were often spared as being "harmless" [12].

Because of the Christian vs. Polytheist rivalry and religious imagery's overwhelming presence in Hellenistic worship, the Church would initially treat visual arts with disdain. During the Synod of Elvira (305-6 CE), nineteen bishops and twenty-six presbyters went so far as to rule the veneration of religious imagery to be heretical [13].

Contrary to the views of some today, early gentile converts did not simply shrug off their former beliefs as being nonexistent. Instead, they had to first demonize their former deities. To better rationalize their transition from Hellenism to Christianity they embraced the concept of demonic deception. They had simply been tricked by the devil to believe in Zeus, offer sacrifices to Mars, or pray to Venus for a compatible mate. Consequently, the destruction of ancient sculptures and mosaics depicting these false gods, and often times the temples that housed them, became somewhat obligatory.

In the year 399 CE, the city of Alexandria would fall to the control of Theophilus, then the Christian patriarch of that city. The historian, Socrates of Constantinople (380-439 CE) goes on to describe what then amounted to cultural genocide which followed. "Seizing this opportunity, Theophilus exerted himself to the utmost... he caused the Mithraeum to be cleaned out... Then he destroyed the Serapeum... and he had the phalli of Priapus carried through the midst of the forum. ...the heathen temples... were therefore razed to the ground, and the images of their gods molten into pots and other convenient utensils for the use of the Alexandrian church [15]".

Consequently, half of the next millennium would be required for art to reestablish itself and yet another millennium still before nudity once again became acceptable. Subsequently, until art was generally condoned by the Church, Hellenistic sculpture and frescoes would continue to be disfigured and, in some lucky instances, just buried. However, not all artwork damaged or destroyed by religious zealots over the ages was restricted to idols or naked figures. Christian would also attack Christian artwork during periods of Byzantine Iconoclasm (726-787 CE and 815-843 CE) and the much later Protestant Reformation periods of iconoclasm (1523-62).

Attacks by Christians on pagan and Christian art would continue for centuries. Many today find these Christian attacks on art and architecture hard to imagine. Yet, as the author and historian Steven Fine states, "Late Antiquity scholars have been astonishingly quiet on this subject" [17].

Intriguingly, still considered vital to classical education by many, nostalgic artwork of mythological Hellenistic depictions began to re-appear in the fifth century, created well after Christianity became the Empire's state religion (380 CE, Edict of Thessalonica) [18]. This interest in the classical aspects of Hellenistic mythology would be heightened yet again during the later Italian Renaissance, a full millennium later.

Lost Arts, Growing Purpose

Patriarch Theophilus's purging of the Hellenistic libraries, temples, and agoras in 399 CE [15], would coincide with a far broader decline in government, standards of living, and education. Historically referred to as the Migration Period, because of the migration of barbarians after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, a climate of ignorance would prevail in Western Europe until the Carolingian Renaissance of the 9th century when public education would be initiated in churches and monasteries.

Moreover, the studies of philosophy, the arts, and science would not resume until universities began to flourish in the 11the century (University of Bologna, 1088). Consequently, until that time, the arts would be limited to highly skilled scribes and the content limited to the Gospel, appearing in carvings and Illuminated Manuscript which began to be introduced in the 5th century. However, even these works would be subject to destruction during the Byzantine iconoclasm to come [16].

A near-naked Christ on the cross would have been scandalous, if not inconceivable, during the first centuries of Christianity. To that point, there exists no evidence of the cross being a symbol of Christianity before Constantine the Great's proclaimed vision before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312 CE [20]. That symbol is today thought to have been the Greek Chi-Rho sign [21], used by Constantine thereafter as his standard or labarum.

The earliest known carving of Jesus attached to a cross is thought to be one carved upon a casket, attrib. Rome, between 420-430 CE [22] (below image at left). However, the first, Church-sanctioned image of the figure of Jesus on a cross is within the illuminated manuscript of the Rabulla Syriac Gospel of 586 CE (below right) more than a century later. Here, in this authorized depiction, the Christ is shown clothed in a columbium tunic. Illuminated manuscripts would not begin to display an unclothed, crucified Jesus until the 7th century.

Regarding early Christianity's abhorrence of sensuality, author, and historian, Kenneth Clark wrote in his "The Nude - A Study in Ideal Form" "...the whole of medieval art is proof of how completely Christian dogma had eradicated image of bodily beauty ...At least there is no doubt about the puritanism of the Christian tradition as we see it. For example, in the first full-size, independent nude figures of medieval art (figure to left), the Adam and the Eve at Bamberg. Their bodies are as little sensuous as the buttresses of a Gothic church. Eve's figure is distinguished from Adam's only by two small, hard protuberance far apart on her chest." [23]

Carolingian Renaissance

The Catholic Church had begun to declare its independence from the Eastern Byzantine Church when Charlemagne was anointed Emperor by Rome's Pope Leo III in 800 CE. This would be the birth of the Holy Roman Empire and the Catholic Church's initial rise above secular power.

After the Great Schism of 1054, between the Eastern Imperial and Western Latin churches, the Catholic Church was born [24]. Seated in Rome Italy, where much of the surviving Greek and Roman pagan artwork of the ancient empire remained, a far more figurative form of art began to flourish. Perhaps not too coincidentally, the age of Universities would shortly dawn upon Europe [25].

Medieval paintings, sculptures, and elaborate architectural relief work began to appear and gradually spread across Western Europe. Depictions of a scantily clad, crucified Christ was by then becoming the work of skilled tradesmen beyond the monastery walls.

The Naked Damned

11th century Italy's artists continued fostering innovations to the rendering of the human form up until its own Renaissance (14-16th centuries). Aside from crucifixions, baptisms and physical acts of passion involving the lives of Jesus and the saints, Genesis' Garden of Eden and the sensationalism of the Last Judgement would greatly contribute to figurative source material.

Once in the afterlife, there would be no need for articles of clothing, at least not for the damned. For those celestially bound, the casual silk tunics of early Christendom [26] would be employed by the artist to accentuate the human form.

The concept of eternal torment would introduce an element of pain to renderings of bare flesh. Used as a device to control the behavior of church members and improve the likelihood of becoming an estate beneficiary, the Church would promote the concept of hell and embrace artistic depictions of damnation [27].

As a variety of unclothed figures began to appear, paintings of the human form would start to display color and depth. Aside from renderings of the naked damned, paintings of Christ's baptism and the first couple of Eden would join the depictions begun with the crucifixion.

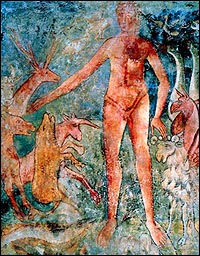

Regarding this 11th Century depiction (to left) of Adam with the creatures of Eden, Art historian, Charles Reginald Dodwell would note a change in fundamental mannerisms: "Adam stands with particular self-assurance as he names the animals, flaunting his nudity in an unabashed and un-medieval way. ...he is endued with roundness and weight by a subtle disposition of flesh tones [28]".

Mannerisms

Cimabue's (1240-1302) Crucifix (1287-88) would herald a new era of the stylized human form. A medieval painter who broke with stiff Byzantine tradition, his elongated figure of Christ exudes a subtle grace and passion. The transparent veil of the loincloth allows us to fully appreciate Christ's form [29], while the twisting anatomy foretells the stylized body movement of a Botticelli, Leonardo, and Michelangelo.

Cimabue would become the teacher of the great Giotto (1267-1337) who, with his realistically structured compositions of grouped individuals, would lay a compositional foundation for the Italian Renaissance. In addition to this, Christians of the very near future would be embracing the athletic human form of the ancient Greek and Roman cultures. Only this time, instead of gods and demigods, it would be Christ, the Virgin, and the holy martyrs.

Giotto would throw open the gates to large-scale religious painting. His numerous church murals would illustrate scenes from the bible and lives of the saints. Giotto’s works would also establish a standard for the appearance of the female form beyond depictions of a single, framed Virgin. Unlike previous artwork, Giotto's women would appear within active roles next to male counterparts. However, much like the text of the New Testament, the overall compositions remained dominated by male figures.

Nevertheless, his semi-nude rendering of Mary Magdalene as she ascends to heaven (The Ecstatic Magdalene c. 1300), located in the lower basilica of Assisi, would become a landmark rendering of the female form. She appears as a "...depiction of female beauty and innocent eroticization in veiled nudity" [30].

Breaking Boundaries

David (1440), was so lifelike, the artist was accused of life-casting. Moreover, the figure's pose was considered extremely erotic, even "homoerotic" [31]. Regarding the reestablishment of nude sculpture as an art form, the work proved a giant cultural leap forward from Theophilus' 4th-century purge of Alexandria.

Aside from Giotto's Mary Magdalene (1330), the depiction of the undraped female form would not be repeated again until the late 15th century. At that time, Italy would begin to dabble in previously forbidden depictions of polytheism. This would only be a temporary reprieve from idolatry granted by the powerful Renaissance statesman/patron, Lorenzo de Medici, who managed to have it shrugged off as mere mythology.

Botticelli's Birth of Venus of 1486 would set a precedent by crossing into the pagan culture and sensual female nudity. It goes further than his own Primavera of 1482, where he depicts a variety of mythological female figures, then rendered in transparent robes. Consequently, the painting barely escaped the wrath of the Dominican fundamentalist, friar Girolamo Savonarola. Savonarola and his followers regularly held Bonfires of the Vanities. Botticelli eventually became sympathetic to Savonarola's cause, painting less as time went on.

The zealous friar would continue to destroy works he deemed sinful as well as art objects he considered overly lavish possession. Sadly, some of Botticelli's works have been said to be used for kindling, though the precise number remains uncertain. Savonarola's brand of iconoclasm would claim some of Florence Italy's greatest art treasures of the day.

Contrapposto Supremo

The Italian Renaissance would reach its climax with the works of Michelangelo, Raphael, and Leonardo. From a figurative standpoint, Michelangelo would reinvent the Greco-Roman Classical interpretation of the human figure. The sculptor/painter would take Greco-Roman mannerisms to the next level by firmly establishing a three-dimensional contrapposto.

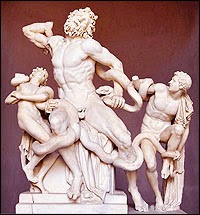

Michelangelo (1475-1564) likely witnessed the Laocoön (c. 200 BCE) being excavated during his time in Rome during in 1506. He would be influenced by it and the dynamic pose of the Belvedere Torso (200-100 BCE), also in Rome at that time. Michelangelo would claim the ancient torso to be his "teacher", others would refer to it as "Michelangelo's Torso" [32].

Michelangelo would incorporate his own variation to this classical pose in his sculpture of David (1504), which is more chiastic balance than contrapposto. However, the slave sculptures to follow were pure Michelangelesque, a robust harmony of chiastic and contrapposto, which would become his signature trademark. Not only would he incline the vertical axis to a greater tilt between the torso and hips, but also introduce a back-and-forth swirling motion, which would sometimes extend upwards to raised arms and/or a tilted head. His Rebellious Slave (1513) demonstrates the most extreme example possible.

From a standpoint of non-controversial expression, this balance proved to be yet another milestone. When Michelangelo took on the ceiling fresco in the Sistine Chapel, it not only enabled him to create one of the most profuse implementations of the human form in all of the arts, it also allowed him to express his figurative vision in one of Christendom's most elite settings, the Pope's private chapel.

The Seeds of Modern Art: A suppressive government, industrial innovations and growing apathy towards Salon sanctioned artwork all contributed to a world-changing artistic rebellion.

Visit this later update by CLICKING HERE

Romanticism and Modern Thought: include key movements that continue to have a lasting impact since the Industrial Revolution and Impressionism. Modern Art is just a few clicks away.

Visit this later update by CLICKING HERE

Art Capitalized: Passions and innovations in painting techniques begin to impact the conservative world of neoclassical art as artists begin to question tradition.

Visit this later update by CLICKING HERE

As liberal-minded as today's art connoisseurs may be, their views regarding nudity pale when compared to the broad attitudes of ancient Greece and her worship of unclothed Hellenistic gods. Modern civilization has yet to become comfortable with the bare human form to a level where it can embrace physical beauty as publicly displayed works of art or be as comfortable as the pre-Christian Greeks with naked (gymnos) Olympian sporting events [1].

Classical Greek art would climax after the death of Alexander the Great (323 BCE) and last almost two centuries until the Roman conquest of the Greek peninsula (146 BCE). The idealized Greek figure was an embodiment of grace and health, beauty, and vitality. For the ancients, the ennoblement and perfection of their natural human state remained a matter of pride and self-assurance.

Subsequently, the appearance of sculpted genitalia or unclothed athletes was a celebration of human beauty, one which issued no negative response or repulsion. To the Athenian mind, clothing was simply decorative, for practical protection or a class distinction. To consider refined works of sculpted or painted figurative arts immodest would have been an uncultured, barbarian [2] response.

|

| Click to enlarge Augustus of Prima Porta - A well- developed and incredibly realistic statue of emperor Augustus, 1st century CE. Vatican Museums |

After Greece came under Roman rule, its artwork, including statues of Hellenistic deities would often be confiscated and imported along with Greek artisans [3] to sculpt, create mosaics, and paint murals of Roman variations on Hellenistic theology. This Roman period of Hellenistic art would often produce sculptures that included highly detailed figurative monuments of Rome's emperors and officials (figure to right). However, even with its high level of finish, ancient Rome would never quite eclipse the earlier Athenian golden age of the human form.

Nevertheless, adoration of the idyllic human form would eventually clash with the chaste modesty of Christian theology and supply fuel to the reverse-persecution efforts of the early Christian Church towards its longtime pagan rivals. The consequences of which was a wholesale rejection of Hellenistic imagery and the willful destruction and disfigurement of ancient masterworks.

Once Christianity spread across Western culture, rendering the unclothed human figure would slow down or cease entirely. Aside from the few surviving frescos and carved symbols found in the Roman catacombs, Christian artwork is barely present until the 4th century. By that time, the relatively new religion had become legalized (Edict of Milan, 313 CE) within the Roman Empire. Later that same century Christianity became the Empire's state religion (Edict of Thessalonica, 380 CE).

The New Religion

As the Abrahamic views of Judaism, Christianity, and eventually Islam began to overwhelm and replace ancient polytheistic sensibilities, all figurative artwork would become forever challenged. With the advent of monotheism, the unveiled natural human form became sinful, wrong, even evil. Male and female gods and goddesses (lower-case g) were replaced by a singular male God (upper-case G). Consequently, no longer a partner of Zeus in the heavens, the social status of the earthly bound female, daughter of Eve, plummeted to that of a second-class citizen, subservient to the now spiritually enlightened male.

Supporting Figures

As gentile Christians began to dominate, their native Hellenistic, polytheistic roots would begin to emerge and govern ecclesiastical matters [8]. Soon, God would not be alone. As the Church filled the heavens of Christendom with martyrs, saints and the Virgin mother deified, so did it begin to embrace artistic subject matter. However, still maintaining some Abrahamic traditions, the male clergy would retain exclusive leadership and the priestess role would be reduced to that of a veiled nun-servant. Consequently, the female figure would, for the most part, assume a supporting role in Christian art.Like the Jews (and the later Muslims), not all early Christians embraced religious artwork [9]. However, once gentiles gathered majority rule within the new religion, the Hellenistic tradition of sculpted and painted deities would slowly re-emerge, but not without ongoing resistance and setbacks.

|

Clement of Alexandria (150-215 CE)

An early Church father and an

outspoken critic of all things related

to Hellenistic beliefs.

|

Even before Emperor Constantine's Edict of Milan of 313 CE, which freed Christians from government persecution, the new religion had spread rapidly across the Roman Empire. Still remembering the faith's Jewish roots and the history of Hellenistic persecution, Clement of Alexandria (150-215 CE), one of the early Church fathers and theologians, referred to all visual arts (not just nudes) as "deadly toys" [9]. However, bear in mind most art up until that time was Hellenistic depictions of Olympian gods, usually unclothed, or non-religious erotica.

Clement went on to criticize the pagan deities themselves for being "bad examples and warnings of what to avoid" [10]. This emphasis on morality and puritanical behavior would become central to Christianity's developing theology. Clement and other church fathers would go to great lengths to distinguish themselves from their Hellenistic, pagan rivals. In one somewhat humorous instance of this extreme, Clement stated: "Let the head of (Christian) men be shaven unless he has curly hair..." [11].

This inevitable polarization was the result of centuries of persecution and mistreatment at the hands of Hellenistic officials. Consequently, in territories where Christianity became dominant, pagan artwork was often mutilated or destroyed. However "nonhuman pagan representations" (vases, animal sculpture, carvings, etc.) were often spared as being "harmless" [12].

Because of the Christian vs. Polytheist rivalry and religious imagery's overwhelming presence in Hellenistic worship, the Church would initially treat visual arts with disdain. During the Synod of Elvira (305-6 CE), nineteen bishops and twenty-six presbyters went so far as to rule the veneration of religious imagery to be heretical [13].

Contrary to the views of some today, early gentile converts did not simply shrug off their former beliefs as being nonexistent. Instead, they had to first demonize their former deities. To better rationalize their transition from Hellenism to Christianity they embraced the concept of demonic deception. They had simply been tricked by the devil to believe in Zeus, offer sacrifices to Mars, or pray to Venus for a compatible mate. Consequently, the destruction of ancient sculptures and mosaics depicting these false gods, and often times the temples that housed them, became somewhat obligatory.

In the year 399 CE, the city of Alexandria would fall to the control of Theophilus, then the Christian patriarch of that city. The historian, Socrates of Constantinople (380-439 CE) goes on to describe what then amounted to cultural genocide which followed. "Seizing this opportunity, Theophilus exerted himself to the utmost... he caused the Mithraeum to be cleaned out... Then he destroyed the Serapeum... and he had the phalli of Priapus carried through the midst of the forum. ...the heathen temples... were therefore razed to the ground, and the images of their gods molten into pots and other convenient utensils for the use of the Alexandrian church [15]".

|

| Click to enlarge Mithras and the Bull, 100 CE - Viewed damaged and restored states. Ostia Antica, Italy [14] |

Wrath of God

During the 8th century, Byzantium was dealing with the first known outbreak of the plague while beset with the rise of Islam and the Caliphate. Consequently, there were those who blamed figurative representations of Christ and the Virgin as vindication for the Moslem's accusations that Christians were idol-worshippers and the plague as well as increased threats of Muslim invasion to be God's punishment. Consequently, Christian art objects and icons were attacked and removed starting in 730 CE [16]. |

| Saint Aemilianus - The 5th Century saint and martyr, shown here instigating instances of iconoclasm. |

Intriguingly, still considered vital to classical education by many, nostalgic artwork of mythological Hellenistic depictions began to re-appear in the fifth century, created well after Christianity became the Empire's state religion (380 CE, Edict of Thessalonica) [18]. This interest in the classical aspects of Hellenistic mythology would be heightened yet again during the later Italian Renaissance, a full millennium later.

Lost Arts, Growing Purpose

Patriarch Theophilus's purging of the Hellenistic libraries, temples, and agoras in 399 CE [15], would coincide with a far broader decline in government, standards of living, and education. Historically referred to as the Migration Period, because of the migration of barbarians after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, a climate of ignorance would prevail in Western Europe until the Carolingian Renaissance of the 9th century when public education would be initiated in churches and monasteries.

Moreover, the studies of philosophy, the arts, and science would not resume until universities began to flourish in the 11the century (University of Bologna, 1088). Consequently, until that time, the arts would be limited to highly skilled scribes and the content limited to the Gospel, appearing in carvings and Illuminated Manuscript which began to be introduced in the 5th century. However, even these works would be subject to destruction during the Byzantine iconoclasm to come [16].

Byzantine Iconoclasm

Eventually, Eastern Byzantium would rail against visual arts, though few in the Latin West would embrace iconoclasm. Subsequently, many Western manuscripts and carvings, chiefly those in Italy, would survive to provide an important foundation for future artwork.Christus Nudus

Only when we consider the figure of Jesus on the cross do we begin to appreciate similar Hellenistic depictions of nude or scantily clad gods. Simultaneously depicting both the human and divine, the near-naked form of Christ becomes a symbol for his dual existence [19]. Unquestioned and embraced by Christians, the crucifix is today a religious gift store commodity. No Christian is sexually aroused or embarrassed by its public presence. Like the early sculptures of scantily clad gods, the crucified Christ has today emerged to become centrally dominant at many Christian religious services, as well as the foremost religious symbol within the homes of the faithful. |

| Chi-Rho - Chi and Rho are the first two letters (ΧΡ) of "Christ" in Greek ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ (Christos). |

The earliest known carving of Jesus attached to a cross is thought to be one carved upon a casket, attrib. Rome, between 420-430 CE [22] (below image at left). However, the first, Church-sanctioned image of the figure of Jesus on a cross is within the illuminated manuscript of the Rabulla Syriac Gospel of 586 CE (below right) more than a century later. Here, in this authorized depiction, the Christ is shown clothed in a columbium tunic. Illuminated manuscripts would not begin to display an unclothed, crucified Jesus until the 7th century.

|

|

| Click to enlarge Adam and Eve of Bamberg - Possibly the two most non-sensuous nude sculptures in all of Christendom. |

Carolingian Renaissance

The Catholic Church had begun to declare its independence from the Eastern Byzantine Church when Charlemagne was anointed Emperor by Rome's Pope Leo III in 800 CE. This would be the birth of the Holy Roman Empire and the Catholic Church's initial rise above secular power.

|

| Click to expand The Life of Saint Remy and the Baptism of Clovis (Detail) - Produced in Reims, late 9th Century. Musée de Picardie, Amiens |

Medieval paintings, sculptures, and elaborate architectural relief work began to appear and gradually spread across Western Europe. Depictions of a scantily clad, crucified Christ was by then becoming the work of skilled tradesmen beyond the monastery walls.

The Naked Damned

11th century Italy's artists continued fostering innovations to the rendering of the human form up until its own Renaissance (14-16th centuries). Aside from crucifixions, baptisms and physical acts of passion involving the lives of Jesus and the saints, Genesis' Garden of Eden and the sensationalism of the Last Judgement would greatly contribute to figurative source material.

Once in the afterlife, there would be no need for articles of clothing, at least not for the damned. For those celestially bound, the casual silk tunics of early Christendom [26] would be employed by the artist to accentuate the human form.

The concept of eternal torment would introduce an element of pain to renderings of bare flesh. Used as a device to control the behavior of church members and improve the likelihood of becoming an estate beneficiary, the Church would promote the concept of hell and embrace artistic depictions of damnation [27].

|

Regarding this 11th Century depiction (to left) of Adam with the creatures of Eden, Art historian, Charles Reginald Dodwell would note a change in fundamental mannerisms: "Adam stands with particular self-assurance as he names the animals, flaunting his nudity in an unabashed and un-medieval way. ...he is endued with roundness and weight by a subtle disposition of flesh tones [28]".

|

| Click to enlarge Cimabue's Crucifix, 1287–88 - Would usher in a new era of stylized figures, breaking with Byzantine tradition. Basilica di Santa Croce, Florence |

Cimabue's (1240-1302) Crucifix (1287-88) would herald a new era of the stylized human form. A medieval painter who broke with stiff Byzantine tradition, his elongated figure of Christ exudes a subtle grace and passion. The transparent veil of the loincloth allows us to fully appreciate Christ's form [29], while the twisting anatomy foretells the stylized body movement of a Botticelli, Leonardo, and Michelangelo.

Cimabue would become the teacher of the great Giotto (1267-1337) who, with his realistically structured compositions of grouped individuals, would lay a compositional foundation for the Italian Renaissance. In addition to this, Christians of the very near future would be embracing the athletic human form of the ancient Greek and Roman cultures. Only this time, instead of gods and demigods, it would be Christ, the Virgin, and the holy martyrs.

|

| Click to enlarge Giotto: Lamentation of Christ - Unlike the flat Byzantine icons, Giotto's works would have depth, perspective and natural groupings of figures, men and women. c1350, Scrovegni Chapel |

Nevertheless, his semi-nude rendering of Mary Magdalene as she ascends to heaven (The Ecstatic Magdalene c. 1300), located in the lower basilica of Assisi, would become a landmark rendering of the female form. She appears as a "...depiction of female beauty and innocent eroticization in veiled nudity" [30].

Breaking Boundaries

David (1440), was so lifelike, the artist was accused of life-casting. Moreover, the figure's pose was considered extremely erotic, even "homoerotic" [31]. Regarding the reestablishment of nude sculpture as an art form, the work proved a giant cultural leap forward from Theophilus' 4th-century purge of Alexandria.

Aside from Giotto's Mary Magdalene (1330), the depiction of the undraped female form would not be repeated again until the late 15th century. At that time, Italy would begin to dabble in previously forbidden depictions of polytheism. This would only be a temporary reprieve from idolatry granted by the powerful Renaissance statesman/patron, Lorenzo de Medici, who managed to have it shrugged off as mere mythology.

Botticelli's Birth of Venus of 1486 would set a precedent by crossing into the pagan culture and sensual female nudity. It goes further than his own Primavera of 1482, where he depicts a variety of mythological female figures, then rendered in transparent robes. Consequently, the painting barely escaped the wrath of the Dominican fundamentalist, friar Girolamo Savonarola. Savonarola and his followers regularly held Bonfires of the Vanities. Botticelli eventually became sympathetic to Savonarola's cause, painting less as time went on.

The zealous friar would continue to destroy works he deemed sinful as well as art objects he considered overly lavish possession. Sadly, some of Botticelli's works have been said to be used for kindling, though the precise number remains uncertain. Savonarola's brand of iconoclasm would claim some of Florence Italy's greatest art treasures of the day.

|

| Click to enlarge Laocoön and His Sons - The Laocoön and other Hellenistic artwork would foretell the passion and suffering depicted in many Christian works. Vatican Museums |

The Italian Renaissance would reach its climax with the works of Michelangelo, Raphael, and Leonardo. From a figurative standpoint, Michelangelo would reinvent the Greco-Roman Classical interpretation of the human figure. The sculptor/painter would take Greco-Roman mannerisms to the next level by firmly establishing a three-dimensional contrapposto.

|

| Click to expand Michelangelesque Contrapposto |

Michelangelesque

"Chiastic Balance" is the vertical counter-positioning of the human torso and the hips. In it's most subtle use, it is created by a standing figure placing weight on one leg, thereby freeing the other to tilt the axes of the hips. Its use dates back to the Kritios Boy of ancient Greece (c. 480 BCE). However, the term "Contrapposto" more accurately refers to a juxtaposed rotation or corkscrew twisting between hips and torso, due to a forward movement of the knee(s), as in the later Venus de Milo (c. 120 BCE). Michelangelo would incorporate his own variation to this classical pose in his sculpture of David (1504), which is more chiastic balance than contrapposto. However, the slave sculptures to follow were pure Michelangelesque, a robust harmony of chiastic and contrapposto, which would become his signature trademark. Not only would he incline the vertical axis to a greater tilt between the torso and hips, but also introduce a back-and-forth swirling motion, which would sometimes extend upwards to raised arms and/or a tilted head. His Rebellious Slave (1513) demonstrates the most extreme example possible.

The Figure Triumphant

By adding a somewhat androgynous quality to his figures, Michelangelo would strike a balance between expression and sensuality so as to not invite criticism from clergy over the immodest depictions. His male figures take on feminine characteristics of grace while his female figures gather masculine bulk, becoming non-sensual so as to perfectly balance the genders against one another.

From a standpoint of non-controversial expression, this balance proved to be yet another milestone. When Michelangelo took on the ceiling fresco in the Sistine Chapel, it not only enabled him to create one of the most profuse implementations of the human form in all of the arts, it also allowed him to express his figurative vision in one of Christendom's most elite settings, the Pope's private chapel.

Additional Reading

Bibliography

- A. J. Arieti, “Nudity in Greek Athletics,” CW 68 (1975), pp. 431-436

- Larissa Bonfante "Nudity as a Costume in Classical Art" American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 93, No. 4 (Oct. 1989), p. 543

- Cyril Bailey, "Phases in the Religion of Ancient Rome, Volume 10", University of California Press, 1932 p. 129

- Alan F. Segal "Rebecca's Children: Judaism and Christianity in the Roman World" Harvard University Press, 1986, p. 68

- Solomon J. Solomon, Art, and Judaism, university of Pennsylvania Press, The Jewish Quarterly Review, 1901, pp. 553-554

- Alan T. Levenson, "The Wiley-Blackwell History of Jews and Judaism", Chapter 9, Early Christianity in a Jewish Contest, "The Gentiles' p. "The Gentiles"

- David C Sim, "How many Jews became Christian in the first century? The Failure of the Christian Mission to the Jews" Australian Catholic University, University of Pretoria, 2005, pp. 417-418

- Frank Viola, George Bama "Pagan Christianity?: Exploring the Roots of Our Church Practices", Chapter 1, Have We really Been Doing It by the Book? Present Testimony Ministry, 2002, p. 6

- Ferguson, John, "Clement of Alexandria". New York: Ardent Media, (1974), ISBN 978-0-8057-2231-4. p. 53

- Ferguson, John, "Clement of Alexandria". New York: Ardent Media, (1974), ISBN 978-0-8057-2231-4. p. 95

- Ferguson, John, "Clement of Alexandria". New York: Ardent Media, (1974), ISBN 978-0-8057-2231-4. p. 98

- Eberhard Sauer, "The Archaeology of Religious Hatred in the Roman and Early Medieval World", Tempus Publishing, Stroud & Charleston 2003, p. 97

- Philip Schaff, "History of the Christian Church, vol. II - Ante-Nicene Christianity AD 100–325" Section 55 "The Councils of..."

- Eberhard Sauer, The Archaeology of Religious Hatred - In the Roman and Early Medieval World, 2003 by Tempius Publishing, 2009 by the Historic Press, p.14

- Socrates Scholasticus, The Ecclesiastical History, from U. Chevalier in his Repertoire des sources historiques du Moyen Age, Bio-bibliographie 187788 and 1894-1903, pp. 133-134

- David Turner, The Politics of Despair: The Plague of 746-747 and Iconoclasm in the Byzantine Empire, pp. 419-420

- Steven Fine, History and the Historiography of Judaism in Roman Antiquity, Koninklijke Brill N, Leiden, ISBN 978-90-09-23817-6, p. 200

- Kurt Weitzmann, Age of Spirituality - Late Antique and Early Christain Art, Thrid to Seventh Century, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1979, p.126

- Dan Le, "The Naked Christ: An Atonement Model for a Body-Obsessed Culture", Pickwick Publications, 2012, p. 174

- Eusebius, "Eusebius' Life of Constantine", Translated by Averil Cameron and Stuart G. Hall, Oxford University Press, 1999, 2002, pp. 206-208

- Steffler, Alva William (2002). Symbols of the Christian Faith. Grand Rapids, Michigan and Cambridge, United Kingdom: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, p. 66

- Kurt Weitzmann, Age of Spirituality - Late Antique and Early Christain Art, Thrid to Seventh Century, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1979, pp 502-503

- Kenneth Clark, The Nude - A Study in Ideal Form, A Doubleday Anchor Book, 1959, Copyright 1956, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, p. 403

- Romilly Jenkins, "Byzantium: The Imperial Centuries, AD 610-1071, Parts 610-1071" p. 336 & p. 348

- Nuria Sanz, Sjur Bergan, "The Heritage of European Universities," Council of Europe Publishing, 2002, p. 131

- M.S. Dimand, "Coptic Tunics in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Metropolitan Museum Studies, 1930, p. 239

- Brooks B. Hull and Frederick "Bold, Hell, Religion and Cultural Change", Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics (JITE), 1994, pp. 448-449

- C. R. Dodwell, "The Pictorial arts of the West", 1993, 800-1200, New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 161

- Christopher Kleinhenz, "Medieval Italy: An Encyclopedia" Volume 1 A-K, Routledge of New York, 2014, p. 461

- Patricia Zupan, "Giotto's Jouissance: The Ecstatic Magdalene, Lower Basilica of Assisi", Semiotics, Middlebury College, Vermont, 1989, p. 206

- Cristelle L. Baskins, Studies in Iconography - Donatello's Bronze 'David': Grillanda, Goliath, Groom, Western Michigan University Publications, Vol. 15, 1993, pp. 113-114

- Eric Scigliano, "Michelangelo's Mountain - The Quest for the Perfection in the Marble quarries of Carrara", Free Press - Simon & Schuster, 2005, p. 281

The Seeds of Modern Art: A suppressive government, industrial innovations and growing apathy towards Salon sanctioned artwork all contributed to a world-changing artistic rebellion.

Visit this later update by CLICKING HERE

Romanticism and Modern Thought: include key movements that continue to have a lasting impact since the Industrial Revolution and Impressionism. Modern Art is just a few clicks away.

Visit this later update by CLICKING HERE

Art Capitalized: Passions and innovations in painting techniques begin to impact the conservative world of neoclassical art as artists begin to question tradition.

Visit this later update by CLICKING HERE